Comma: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

A '''comma''' is a small difference between two [[stack]]s of similar or dissimilar simpler [[Just intonation|just intervals]], or a difference between intervals belonging to the same category but reached differently. For instance, a stack of three [[6/5]] minor thirds differs from a stack of two [[4/3]] perfect fourths by the interval 250/243, the [[porcupine]] comma; or two distinct wholetones of [[9/8]] and [[10/9]] differ by the interval 81/80, the [[syntonic comma]]. While commas are written as fractions (or [[Interval space#Monzos|monzos]]), most of their useful properties and characteristics come from their role as a separator, rather than the literal fraction they evaluate to. | A '''comma''' is a small difference between two [[stack]]s of similar or dissimilar simpler [[Just intonation|just intervals]], or a difference between intervals belonging to the same category but reached differently. For instance, a stack of three [[6/5]] minor thirds differs from a stack of two [[4/3]] perfect fourths by the interval 250/243, the [[porcupine]] comma; or two distinct wholetones of [[9/8]] and [[10/9]] differ by the interval 81/80, the [[syntonic comma]]. While commas are written as fractions (or [[Interval space#Monzos|monzos]]), most of their useful properties and characteristics come from their role as a separator, rather than the literal fraction they evaluate to. | ||

Each comma serves as the separation between many different pairs of intervals. 9/8 and 10/9 differ by 81/80, but so do [[5/1]] and a stack of four [[3/2]] perfect fifths, and so do [[5/3]] and [[27/16]], and so on. These therefore become an important characteristic of the way just intervals are approximated in a given [[tuning system]]: if a comma vanishes to nothing (we say that the comma is ''tempered out''), structural distinctions are lost in very particular and consistent places; while if a comma is exaggerated beyond its justly-tuned size, these often subtle differences are made much more prominent by the tuning system. A comma is said to be ''observed'' ( | Each comma serves as the separation between many different pairs of intervals. 9/8 and 10/9 differ by 81/80, but so do [[5/1]] and a stack of four [[3/2]] perfect fifths, and so do [[5/3]] and [[27/16]], and so on. These therefore become an important characteristic of the way just intervals are approximated in a given [[tuning system]]: if a comma vanishes to nothing (we say that the comma is ''tempered out''), structural distinctions are lost in very particular and consistent places; while if a comma is exaggerated beyond its justly-tuned size, these often subtle differences are made much more prominent by the tuning system. A comma is said to be ''observed'' (less commonly ''emancipated'') if it is not tempered out, i.e. represents a salient distinction within a tuning system. | ||

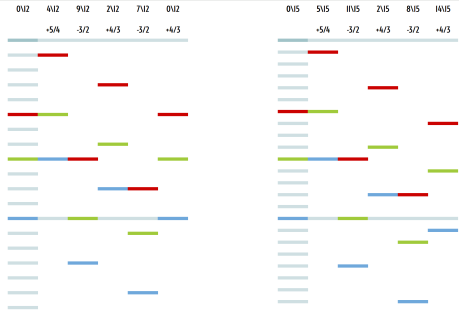

[[File:Qeyqry.png|thumb|459x459px|An example of a comma pump: in [[12edo]], which tempers out 81/80, this progression returns to the starting note; in [[15edo]], which | [[File:Qeyqry.png|thumb|459x459px|An example of a comma pump: in [[12edo]], which tempers out 81/80, this progression returns to the starting note; in [[15edo]], which observes this comma, it does not.]] | ||

Every [[Regular temperament|regular]] way of setting equivalences between intervals, including [[equal temperament]]s, can also be defined in terms of tempering out a specific set of commas (the ''comma basis''), which provides the most compact formalism for a temperament at the costs of obfuscation of the generating structure and non-uniqueness of the basis. In musical terms, every time two sequences of movements by intervals, played as represented in the temperament, would differ by one of these commas if they were played in just intonation, their result is identical. A series of musical progressions relying on this equivalence is called a ''comma pump''; knowing if a progression pumps a comma helps determine which tuning systems it can be played in without issue and which systems require modification to it. | Every [[Regular temperament|regular]] way of setting equivalences between intervals, including [[equal temperament]]s, can also be defined in terms of tempering out a specific set of commas (the ''comma basis''), which provides the most compact formalism for a temperament at the costs of obfuscation of the generating structure and non-uniqueness of the basis. In musical terms, every time two sequences of movements by intervals, played as represented in the temperament, would differ by one of these commas if they were played in just intonation, their result is identical. A series of musical progressions relying on this equivalence is called a ''comma pump''; knowing if a progression pumps a comma helps determine which tuning systems it can be played in without issue and which systems require modification to it. | ||

Finding where useful commas are in a structure focusing on particular intervals | Finding where useful commas are in a structure focusing on particular intervals — fundamentally implying mathematical "coincidences" — is highly nontrivial, but it can be said for example that a large number of commas can be expressed in terms of differences between nearby [[superparticular]] intervals. See [[Mathematics of commas]] for a deeper exploration of this subject. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:57, 15 December 2025

A comma is a small difference between two stacks of similar or dissimilar simpler just intervals, or a difference between intervals belonging to the same category but reached differently. For instance, a stack of three 6/5 minor thirds differs from a stack of two 4/3 perfect fourths by the interval 250/243, the porcupine comma; or two distinct wholetones of 9/8 and 10/9 differ by the interval 81/80, the syntonic comma. While commas are written as fractions (or monzos), most of their useful properties and characteristics come from their role as a separator, rather than the literal fraction they evaluate to.

Each comma serves as the separation between many different pairs of intervals. 9/8 and 10/9 differ by 81/80, but so do 5/1 and a stack of four 3/2 perfect fifths, and so do 5/3 and 27/16, and so on. These therefore become an important characteristic of the way just intervals are approximated in a given tuning system: if a comma vanishes to nothing (we say that the comma is tempered out), structural distinctions are lost in very particular and consistent places; while if a comma is exaggerated beyond its justly-tuned size, these often subtle differences are made much more prominent by the tuning system. A comma is said to be observed (less commonly emancipated) if it is not tempered out, i.e. represents a salient distinction within a tuning system.

Every regular way of setting equivalences between intervals, including equal temperaments, can also be defined in terms of tempering out a specific set of commas (the comma basis), which provides the most compact formalism for a temperament at the costs of obfuscation of the generating structure and non-uniqueness of the basis. In musical terms, every time two sequences of movements by intervals, played as represented in the temperament, would differ by one of these commas if they were played in just intonation, their result is identical. A series of musical progressions relying on this equivalence is called a comma pump; knowing if a progression pumps a comma helps determine which tuning systems it can be played in without issue and which systems require modification to it.

Finding where useful commas are in a structure focusing on particular intervals — fundamentally implying mathematical "coincidences" — is highly nontrivial, but it can be said for example that a large number of commas can be expressed in terms of differences between nearby superparticular intervals. See Mathematics of commas for a deeper exploration of this subject.